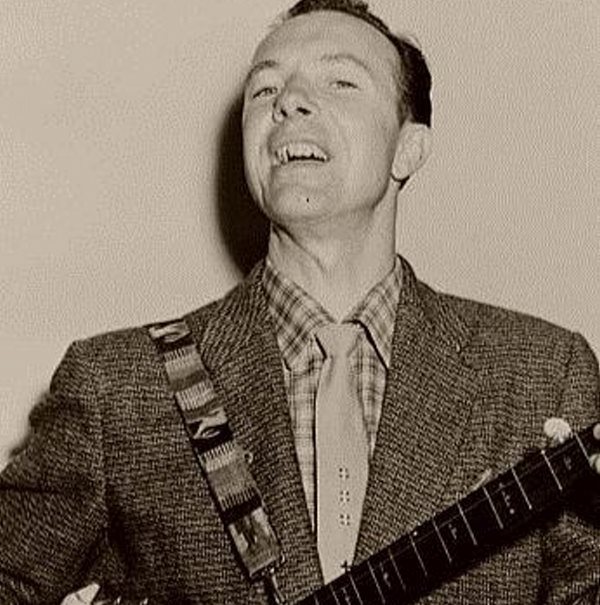

PETE SEEGER

Biography

Pete Seeger. Musician, singer, songwriter, folklorist, labor activist, environmentalist, and peace advocate, Seeger was born in Patterson, New York, son of Charles and Constance Seeger, whose families traced their ancestry back to the Mayflower. Seeger grew up in an unusually politicized environment. His father, Charles, had been a music professor at the University of California at Berkeley, where his pacifism won him so many enemies that he quit teaching in the fall of 1918.

At thirteen, Pete Seeger became a subscriber to the New Masses. His heroes were Lincoln Steffens and Mike Gold, and he aspired to a career in journalism. In 1936 he heard the five-string banjo for the first time at the Folk Song and Dance Festival in Asheville, North Carolina, and his life was changed forever.

Pete Seeger spent two unhappy years at Harvard and left before final exams in the spring of 1938. He made his way to New York, where he eventually landed a job with the Archives of American Folk Music. Seeger spent 1939 and 1940 seeking out legendary folk-song figures such as the blues singer Leadbelly and labor militant Aunt Molly Jackson. By 1940 he had become quite an accomplished musician, thanks in no small part to his enormous self-discipline and Puritan rectitude.

On March 3, 1940, a date folklorist Alan Lomax once said could be celebrated as the beginning of modern folk music, Seeger met Woody Guthrie at a “Grapes of Wrath” migrant-worker benefit concert. In 1940 the duo helped form the Almanac Singers, a loosely organized musical collective that included Lee Hays, Millard Lampell, Sis Cunningham, Sonny Terry, Brownie McGhee, and others.

The Almanac Singers initially recorded labor songs like “The Talking Union Blues,” which they created as an organizing song for the CIO. The Almanacs also recorded pacifist tunes like “The Ballad of October 16,” in retrospect an embarrassingly shrill attack on Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt and the effort to prepare for the war against fascism.

With the entry of the United States into World War II and the creation of the U.S.-Soviet alliance, the Almanacs suddenly attained respectability. They appeared on a coast-to-coast radio broadcast, the William Morris Advertising Agency offered to help with publicity, and the group was invited to sing in some of New York’s poshest nightclubs. The allure of success posed a problem for Pete Seeger and the Almanacs that has been a particularly nettlesome one for him and artists on the Left: What concessions can or should an artist make to a mass audience without loss of artistic integrity and political radicalism?

By the time Pete Seeger was drafted in 1942, however, critics had called attention to the Almanacs’ ties, and the FBI had already begun to fill what is no doubt a very fat file on the tall, skinny balladeer. While on his first leave from the Army, Seeger also married Tashi Ohta, who virtually all of their friends agree played a crucial role in organizing Seeger’s career and managing his finances.

Pete Seeger was apparently not entangled in the sectarian squabbling that contributed to the Communist Party’s weakness at the end of WW II. He had joined the Party in 1942 and would depart about 1950, but like many artists within the Party orbit, he was often viewed as unreliable.

But regardless of Seeger’s feelings about the Party, it didn’t take him very long to realize that amidst the paranoia and reaction of the Cold War, the union movement had no interest in associating itself with singing radicals.

By 1950 Hays and Seeger, along with Fred Hellerman and Ronnie Gilbert, formed the Weavers and enjoyed instant success with highly sweetened versions of “Goodnight Irene” and other folk tunes.

Just as quickly as the Weavers topped the charts, however, their career was torpedoed by blacklisting, Red-baiting, and numerous cancellations of their performances at the last minute. Pete Seeger spent the fifties defining and nurturing his own audience. He still performed occasionally with the Weavers, but he mainly supported his family with appearances on the college circuit and at Left summer camps. He also recorded five to six albums per year for Folkways Records.

In 1955 Pete Seeger was subpoenaed by the House Un-American Activities Committee and became one of the few witnesses called that year who didn’t invoke the Fifth Amendment. In a dramatic appearance before the committee, Seeger claimed that to discuss his political views and associates violated his First Amendment rights.

The following year, which saw Pete Seeger compose “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?”, Seeger, Arthur Miller, and six others were indicted for contempt of Congress by an overwhelming vote in the House of Representatives. In 1961 he was found guilty of contempt and on April 2 he was sentenced to ten years in prison. The following year his ordeal ended when the case was dismissed on a technicality.

Pete Seeger had cultivated a folk music revival in the 1950s, and the movement gathered momentum from 1958 into the early 1960s. ABC decided to cash in on the craze with a weekly television show, Hootenanny, but enthusiasm for the program waned when it was discovered that Seeger had been blacklisted and would not be permitted to appear.

Pete Seeger spent a considerable amount of time in the South during the civil rights marches of the 1960s. It was his variation of an old spiritual, which Seeger called “We Shall Overcome,” that has become an anthem of the crusade for equality in America.

The Vietnam War deeply and personally offended Seeger, who used his network television return on the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour to air a scathing attack on Lyndon Johnson’s war policies, “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy.” The song was cut by network censors, but Seeger made a second appearance on the program and sang the song without interruption.

Like many Old Leftists, Seeger was not entirely comfortable with the cultural radicalism of the 1960s. He disliked the generational tensions fostered by the movement (he once recorded a song called “Be Kind to Parents”) and repeatedly advised young radicals to avoid divisions along generational lines.

Amidst the mud and despair of Resurrection City, an effort by the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s followers to carry out his dream of establishing a poor people’s community in Washington and focusing the nation’s attention on the problems of the poor, Seeger began to question the validity of his activism. In the 1970s and 1980s he continued to perform benefits for causes too diverse to list, but increasingly Seeger focused his attention on environmental issues.

When Pete Seeger and his friends launched the sloop Clearwater into the Hudson River in 1969, he was in effect fulfilling a lifelong love of the outdoors and a longstanding desire to do something to clean up the environment polluted by irresponsible corporate and public water usage.

Pete Seeger has become a highly visible and much beloved figure in American life. He has issued some one hundred records, written and collaborated on numerous radical songbooks, articles, and technical manuals on playing the banjo. Fifty years after the Popular Front, Seeger is one of the last links with the optimistic and expansive culture of Depression-era America.

Pete And Five Strings, Pete Seeger

Pete And Five Strings, Pete Seeger Peter, Paul & Mary, 1962

Peter, Paul & Mary, 1962 Ballroom, Country, Bailes de Salón

Ballroom, Country, Bailes de Salón