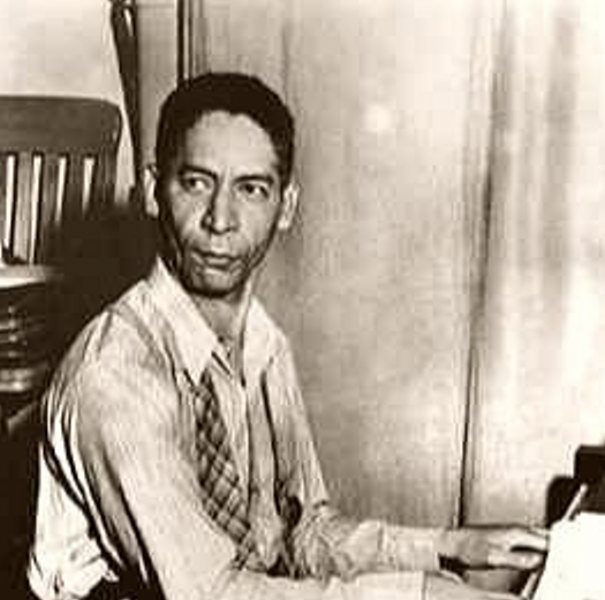

JELLY ROLL MORTON

Biography

Widely recognized as a pivotal figure in early jazz, Morton is perhaps most notable as jazz’s first arranger, proving that a genre rooted in improvisation could retain its essential spirit and characteristics when notated. His composition “Jelly Roll Blues” was the first published jazz composition, in 1915.

Jelly Roll Morton was born into a Creole of Color family in the Faubourg Marigny neighborhood of downtown New Orleans, Louisiana. Sources differ as to his birth date: a baptismal certificate issued in 1894 lists his date of birth as October 20, 1890; Morton and his half-sisters claimed he was born on September 20, 1885[citation needed]. His World War I draft registration card showed September 13, 1884, but his California death certificate listed his birth as September 20, 1889. He was born to F. P. Lamothe and Louise Monette (written as Lemott and Monett on his baptismal certificate). Eulaley Haco (Eulalie Hécaud) was the godparent. Hécaud helped choose his christening name of Ferdinand. His parents lived in a common-law marriage and not legally married. No birth certificate has been found to date.

At the age of fourteen, Jelly Roll Morton began working as a piano player in a brothel (or as it was referred to then, a sporting house.) While working there, he was living with his religious,church-going great-grandmother; he had her convinced that he worked as a night watchman in a barrel factory.

In that atmosphere, he often sang smutty lyrics; he took the nickname “Jelly Roll”, which was black slang for female genitalia.

“When my grandmother found out that I was playing jazz in one of the sporting houses in the District, she told me that I had disgraced the family and forbade me to live at the house… She told me that devil music would surely bring about my downfall, but I just couldn’t put it behind me.”

Around 1904, Jelly Roll Morton also started touring in the American South, working with minstrel shows, gambling and composing. His works “Jelly Roll Blues”, “New Orleans Blues”, “Frog-I-More Rag”, “Animule Dance”, and “King Porter Stomp” were composed during this period. He got to Chicago in 1910 and New York City in 1911, where future stride greats James P. Johnson and Willie “The Lion” Smith caught his act, years before the blues were widely played in the North.

Jelly Roll Morton was invited to play a new Vancouver nightclub called The Patricia, on East Hastings Street. The jazz historian Mark Miller described his arrival as “an extended period of itinerancy as a pianist, vaudeville performer, gambler, hustler, and, as legend would have it, pimp”.

Jelly Roll Morton returned to Chicago in 1923 to claim authorship of his recently published rag, “The Wolverines”, which had become a hit as “Wolverine Blues” in the Windy City. He released the first of his commercial recordings, first as piano rolls, then on record, both as a piano soloist and with various jazz bands.

They moved that year to New York City, where Morton continued to record for Victor. His piano solos and trio recordings are well regarded, but his band recordings suffer in comparison with the Chicago sides, where Morton could draw on many great New Orleans musicians for sidemen. Although he recorded with the noted musicians clarinetists Omer Simeon, George Baquet, Albert Nicholas, Wilton Crawley, Barney Bigard, Lorenzo Tio and Artie Shaw, trumpeters Bubber Miley, Johnny Dunn and Henry “Red” Allen, saxophonists Sidney Bechet, Paul Barnes and Bud Freeman, bassist Pops Foster, and drummers Paul Barbarin, Cozy Cole and Zutty Singleton, Morton generally had trouble finding musicians who wanted to play his style of jazz. His New York sessions failed to produce a hit.

In 1935, Jelly Roll Morton moved to Washington, D.C., to become the manager/piano player of a bar called, at various times, the “Music Box”, “Blue Moon Inn”, and “Jungle Inn” in the African-American neighborhood of Shaw. (The building that hosted the nightclub stands at 1211 U Street NW.) Morton was also the master of ceremonies, bouncer, and bartender of the club. He lived in Washington for a few years; the club owner allowed all her friends free admission and drinks, which prevented Morton from making the business a success.

In 1938 Morton was stabbed by a friend of the owner and suffered wounds to the head and chest. After this incident his wife Mabel demanded that they leave Washington.

Sample of Morton’s introduction and performance of the piece, with its innovative moving tone cluster evoking a tiger’s growl

Problems listening to this file? See media help.

During Morton’s brief residency at the Music Box, the folklorist Alan Lomax heard the pianist playing in the bar. In May 1938, Lomax invited Morton to record music and interviews for the Library of Congress.

Lomax was very interested in Morton’s Storyville days and the ribald songs of the time. Although reluctant to recount and record these, Morton eventually obliged Lomax. Because of the suggestive nature of the songs, some of the Library of Congress recordings were not released until near the end of the 20th century.

In his interviews, Jelly Roll Morton claimed to have been born in 1885. He was aware that if he had been born in 1890, he would have been slightly too young to make a good case as the inventor of jazz. He said in the interview that Buddy Bolden played ragtime but not jazz; this is not accepted by the consensus of Bolden’s other New Orleans contemporaries. The contradictions may stem from different definitions for the terms ragtime and jazz. These interviews, released in different forms over the years, were released on an eight-CD boxed set in 2005, The Complete Library of Congress Recordings. This collection won two Grammy Awards. The same year, Morton was honored with the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award.

When Jelly Roll Morton was stabbed and wounded, a nearby whites-only hospital refused to treat him, as the city had racially segregated facilities. He was transported to a black hospital further away. When he was in the hospital, the doctors left ice on his wounds for several hours before attending to his eventually fatal injury. His recovery from his wounds was incomplete, and thereafter he was often ill and easily became short of breath. Morton made a new series of commercial recordings in New York, several recounting tunes from his early years that he discussed in his Library of Congress interviews.

Worsening asthma sent him to a New York hospital for three months at one point. He continued to suffer from respiratory problems when visiting Los Angeles with a series of manuscripts of new tunes and arrangements, planning to form a new band and restart his career. Jelly Roll Morton died on July 10, 1941 after an eleven-day stay in Los Angeles County General Hospital.

According to the jazz historian David Gelly in 2000, Morton’s arrogance and “bumptious” persona alienated so many musicians over the years that no colleagues or admirers attended his funeral. But, a contemporary news account of the funeral in the August 1, 1941 issue of Downbeat says that fellow musicians Kid Ory, Mutt Carey, Fred Washington and Ed Garland were among his pall bearers. The story notes the absence of Duke Ellington and Jimmie Lunceford, both of whom were appearing in Los Angeles at the time. (The article is reproduced in John Lomax’s biography of Morton, Mister Jelly Roll, University of California Press, 1950.) Morton is buried in Calvary Cemetery, 4201 Whittier Blvd, Los Angeles, California, Section N, Lot 347, grave #4,in the north west quadrant of the cemetery.

Jelly Roll's Jazz, Lawson-Haggart Jazz Band

Jelly Roll's Jazz, Lawson-Haggart Jazz Band Jelly Roll Morton, Jelly Roll Morton

Jelly Roll Morton, Jelly Roll Morton Jelly Roll Morton

Jelly Roll Morton Smilin´The Blues Away, Jelly Roll Morton

Smilin´The Blues Away, Jelly Roll Morton 100 Jazz Grand Reserve

100 Jazz Grand Reserve Art Decó Vocal Jazz of the 30

Art Decó Vocal Jazz of the 30